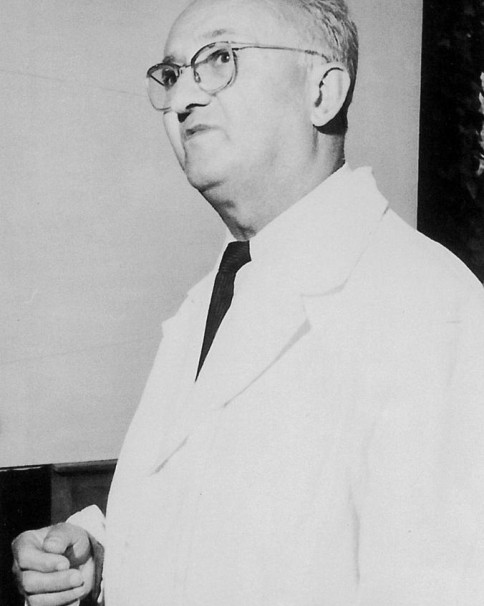

Léon Tutundjian was born in Amasya (Anatolia). It was a cultivated family: his mother was a primary school teacher, his father taught physics and chemistry. It was from him Léon acquired his love of science that would later become a source of inspiration.

His father, an accomplished violinist, taught him the violin which he played all his life. He started painting at the age of 14 and then studied ceramics at the Istanbul school of fine arts. Fleeing the Armenian genocide at the age of 17, he found refuge in an Armenian monastery on the island of San Lazzaro in Venice, where he continued his studies. As his sense of his artistic vocation grew, he began to dream of going to Paris, the capital of the arts. He arrived in the city in 1924 and found employment as a ceramics worker.

1924-1925

It was not long before he befriended the artists Ervand Kotchar, a fellow Armenian, and then through him, the Georgian David Kakabadzé, their elder. These two artists would have an important influence on Tutundjian’s work, both on his plastic expression and by revealing to him the potential of certain techniques (spraying paint with an airbrush, stamping on silk and three-dimensional wall sculpture).

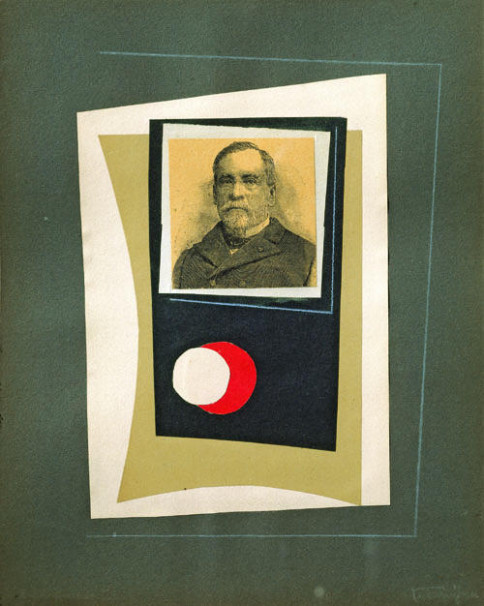

Tutundjian’s early works are of great diversity. He tries his hand at figurative art, cubism, and collage. But already, the specificity of his “language” is emerging, which makes his works easily identifiable.

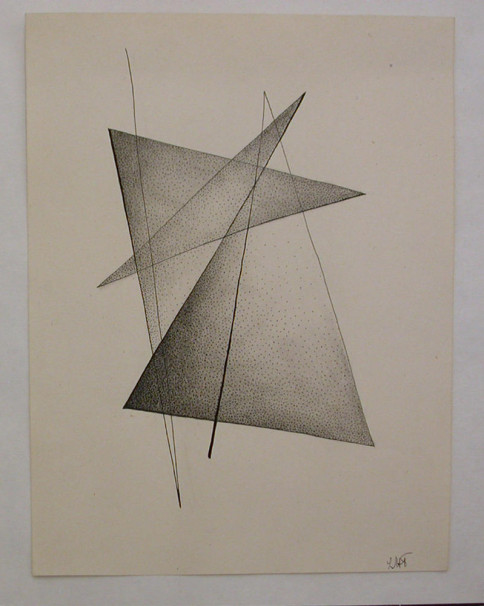

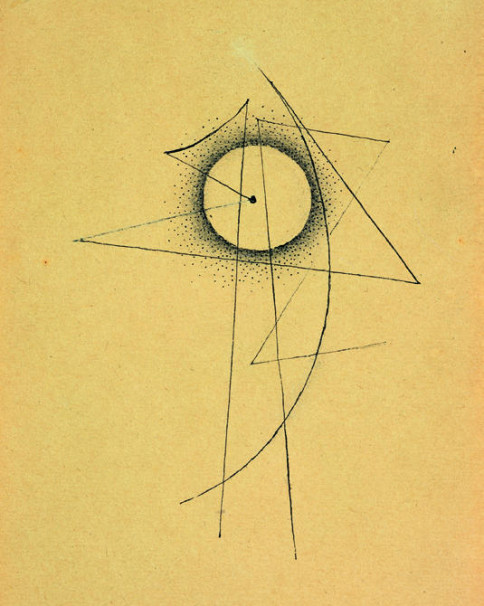

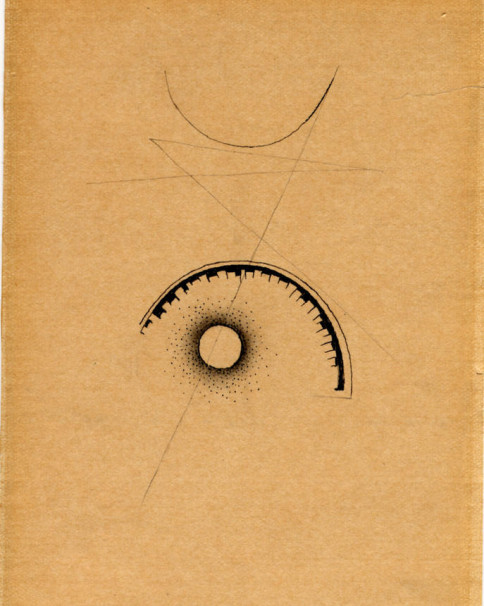

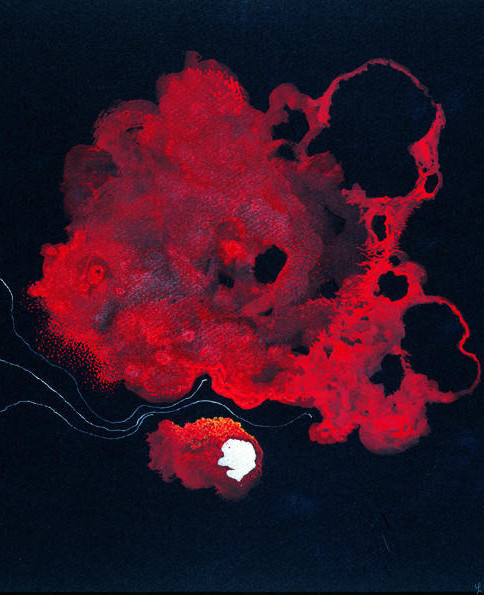

Often he “drowns” his drawings, always precise and rigorous, in a coloured Tachism, a mixture of various oxidations of the paper. Soon, backgrounds created with the airbrush technique appear in his gouaches and watercolours, which, combined with clouds of points, allows him to tend towards a poetic, unreal, perhaps “surreal” universe.

From 1926 Onwards

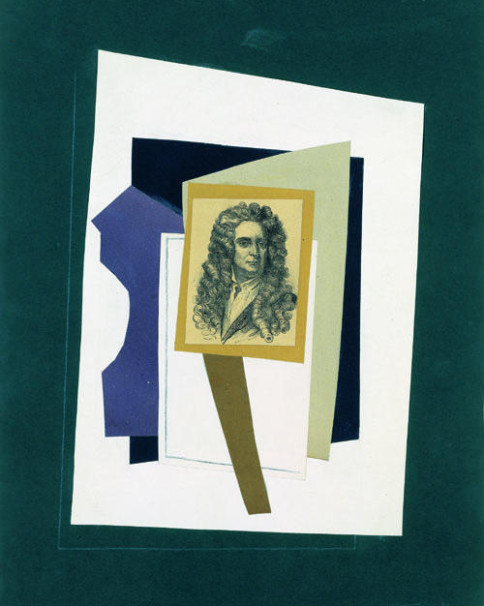

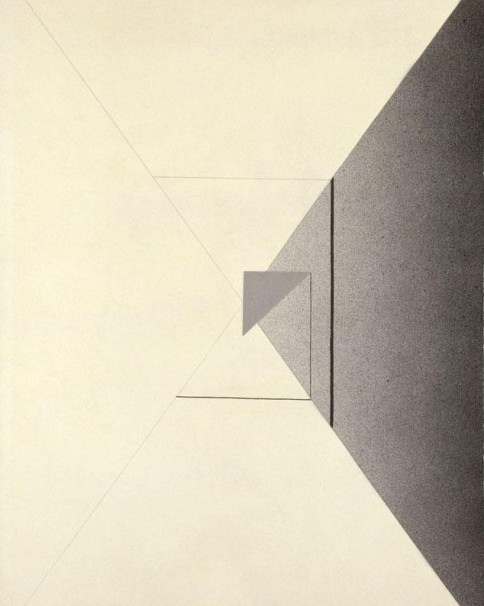

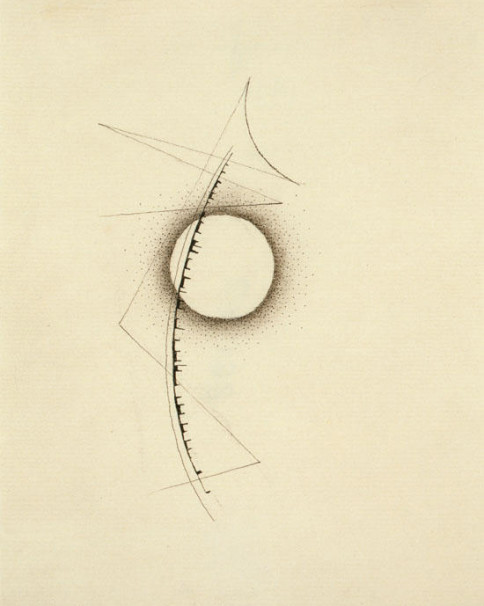

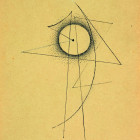

In 1926, he turned to geometric and organic abstraction. His drawings in Indian ink are numerous and always perfectly executed; he plays with lines, half-moons, circles, and, again, his works are nothing like those of other artists.

“Geometry is never rigid, nor strict, and seems rather sensitive and dreamlike. All these lines, verticals, circles, are drawn by hand, without ruler or compass; the lines vibrate…” (Gladys Fabre, Tutundjian, Editions du Regard, Paris, 1994).

Around 1928

It was essentially in 1928 that he created his “reliefs”, three-dimensional mural sculptures.

With an extreme economy of means, he created works on a wooden base, in grey or black, from iron domes, rods, tubes, cylinders.

“Tutundjian uses a limited vocabulary of shapes, often modular, in various sizes and positions, he plays on the positive and negative of inverted domes, or the full and hollow of cylinders. The rhythm of circular volumes is opposed to that of lines…” (Gladys Fabre, id.)

Although small in size, the monumentality of his “reliefs” is easily visible.

It is these works, and his involvement in the creation of the Concrete Art movement, that would allow Tutundjian to be spotted by his most prominent peers of the time, and give him access to several avant-garde artistic events in Europe.

Helion wrote about his friend Tutundjian: “The exhibition at the Bonaparte Gallery made a violent impression on the small world of people tormented by a new art. His works were unlike anything known here. I think I can testify to the admiration that artists who have since become very famous had for him at the time…”. We think of Giacometti, Arp, Calder, Miro, Van Doesbourg, etc… And the similarities between the works of these artists and those of Tutundjian are sometimes striking.

From the 1930s to 1959

In 1932, Tutundjian resigned from the Abstraction-Creation movement and moved entirely towards surrealist figuration.

In radical contrast to his early work, his new paintings are mostly very colourful, and strongly “filled” with a very diversified iconography.

On the basis of great technical mastery, he often uses the process of representing the painting within the painting, like Magritte or De Chirico in the same period.

The Second World War and its attendant suffering and horrors challenged the hierarchy of concerns; although stateless, Tutundjian was mobilized; he was soon wounded. When he returned, he devoted himself mainly to ceramics to support his family until the end of the war.

The evolution towards surrealism was experienced by Tutundjian as a natural progression, a necessity to return to “more human”, in a kind of symbolic and metaphysical synthesis.

He also seeks to recapitulate his journey by reintegrating the geometric period, the landscapes of his native Armenia, into the contemporary surrealist work.

But, adhering with difficulty to the dogmatism of the “popes” of surrealism, like Breton, he could not merge into the movement; he therefore found himself marginalized.

This was to have a decisive and damaging impact on his “career”.

1959-1968

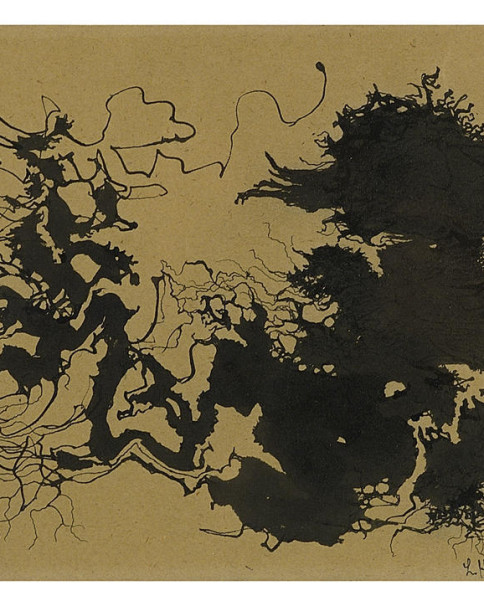

Abandoning surrealism, he returned to abstraction in 1959.

Until his death in 1968, he produced many drawings, often “pastellised”, canvases, as well as some reliefs, reviving his non-conformism and early sensitivity.

Link to Léon Tutundjian Foundation