Leonid Davydovich Baranoff[1] was born in 1888 into a middle-class Jewish family in the small Ukrainian town of Bolshaya Lepetikha (in Ukrainian, Velyka Lepetikha in the Kherson Oblast). Because his father was sufficiently well off to educate his children well (Vladimir’s brother became a doctor, his sister a pharmacist), he was able to study at the art xchool in Odessa between 1903 and 1908. At the time, this was the only institution in the region in any way receptive to certain ideas of modern European art, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Baranoff received a solid artistic training there, which encouraged him to draw on the French pictorial movements of the late nineteenth century. Many of his teachers belonged to the Wanderers group (Péredvijniki) who practised plein air painting while developing a specifically Russian conception of landscape. Unlike the French impressionists, they saw their works as having a real educational role for the viewer and a critical role with regard to the Russian society of the day. This initial training was supplemented by reading art magazines, in particular Mir iskusstva (The World of Art), which published articles on current Russian and European art and argued the need for a pictorial renewal of Russian art, inspired in particular by art nouveau and symbolism.

The young artist’s first works (family portraits, local landscapes) evince his early passion for colour. Already at that time, they were more in line with trends in Western painting than with the lyrical and realistic painting of the Wanderers. This was probably due to his early contacts with the local avant-garde.

In 1907, he was invited by the brothers Vladimir and David Burliuk and Mikhail Larionov to take part in the “Stephanos”[2] exhibition (also known as “the first anti-traditionalist exhibition”) in Moscow, alongside other rising figures of the avant-garde such as Natalia Goncharova, Aristarkh Lentulov, Georgy Yakulov, Leopold Stürzwage (later Survage) and Nikolai Sapunov, whose common ambition was to renew Russian painting. The work of these artists, especially Larionov, became a model for the young Baranoff, encouraging him to follow on the path of impressionism, post-impressionism and fauvism, whose principles he assimilated in order to better develop his own style.

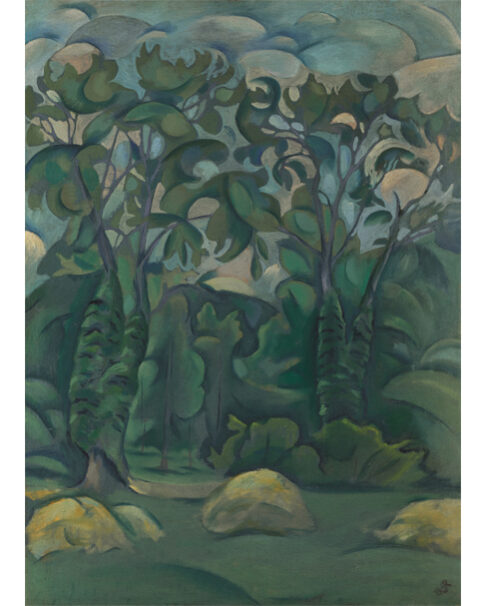

Rather than attempt to render forms precisely he suggested their relief, often by using complementary colours. These he did not mix on either the canvas or the palette, but instead juxtaposed in order to produce effects of light and shadow, thus proving his mastery of the principle of optical mixing derived from the theory developed by Chevreul and practised by the pointillists. At the same time, Baranoff’s early paintings also show an interest in Ukrainian folklore and pictorial traditions, as well as his familiarity with the paintings of the Russian landscape masters.

After graduating from the school in Odessa in May 1908, the artist continued his studies at the Academy of Saint Petersburg (directed at the time by Ilya Repin, leader of the Wanderers), from which he was quickly expelled due to absenteeism, which was certainly caused by his closeness to avant-garde circles, which he joined at several events. In 1908, he had work in the XVth Painting Exhibition of the Union of Russian Artists Moscow and the “Zveno” (Link) exhibition, also known as the “Exhibition of Angry Young Artists,” organised by David Burliuk (who published his manifesto The Voice of Impressionism on this occasion), bringing together not only painters, but also sculptors and poets who showed their works in the street, in a sort of proto-performance art. The following year, together with Burliuk, Alexandra Exter, and Lentulov, he took part in the “Venok-Stephanos” exhibition in St. Petersburg, and then in the “Impressionist” exhibitions in Kherson, St. Petersburg and Vilnius. At the latter, his two paintings entitled Sun were noticed by a critic in a local newspaper:

“In two of his paintings called Sun, Baranoff has given an excellent example of the latest Impressionist-Pointillist painting. He uses a special technique to convey the ether, the eternal movement of the air: by painting dots and marks. Baranoff’s sunset is an example of this kind of painting and his work is very interesting for the art scene.”[3]

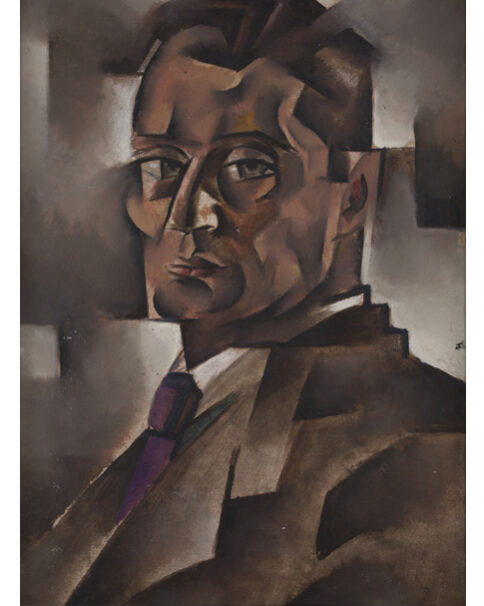

In 1910, the young artist, like many of his predecessors, decided to go to Paris to complete and perfect his education. During this first stay there, which lasted four years, he lived, among other places, at La Ruche (from 1912 to 1913). Under the name Daniel Rossiné he was a regular participant in Parisian events such as the Salon d’Automne and Salon des Indépendants. At that time, the local art scene was marked by the recent emergence of Cubism as a new avant-garde. This immediately influenced Baranoff’s own work. At first, he drew mainly on Cézannean cubism, its geometrisation of volumes, its architectural construction of space and absence of perspective. His colour palette, however, was more reminiscent of Ukrainian folklore, the art of Van Gogh and the experiments of the Fauves.

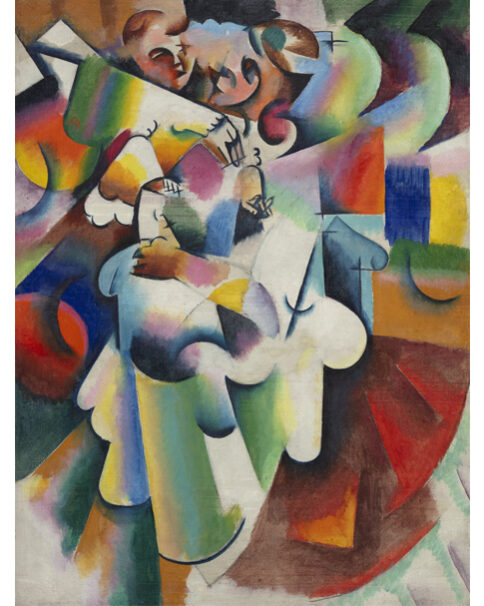

From 1910, he grew close to Sonia and Robert Delaunay, who became his friends and protectors, introducing him to the Russian and Ukrainian community in Paris and to local avant-garde circles, which often met at the salon of Baroness Helene d’Oettingen. Through them he met fellow countrymen Léopold Survage, Serge Férat, Alexander Archipenko, and Marc Chagall, but also Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso and the cubists of the future Golden Section group (Gleizes, Metzinger, Le Fauconnier). Thanks to these contacts, he exhibited in the Cubist Room at the 1911 Salon des Indépendants, the first public and collective exhibition by the cubists, alongside Delaunay, Gleizes, Léger, Le Fauconnier and Metzinger. The Forge, the painting shown on this occasion, belongs to the cubo-futurist period of Baranoff’s work. It bears witness to his fascination with rhythm, the combination of static and dynamic elements and the fragmentation of the colour scale that he shared with the Italian Futurists, who were also present on the Parisian scene at the time.

In 1912, he produced two further series of paintings on biblical subjects: Adam and Eve and Apocalypse, which were the direct result of his contacts with the Delaunays, who were themselves involved in simultaneism and orphism at the time, with the idea of going beyond the limits of the cubism of Braque and Picasso and, through the in-depth examination of light, creating an autonomous language of colour. In the years following the completion of these two cycles – still bearing the reminiscences of Michelangelo, Cézanne’s Bathers and the styles of Larionov, Goncharova and Burliuk – Rossiné began to create polychrome sculptures. These works which he exhibited these at the Salon des Indépendants in 1913 and 1914 (Symphony) bring to mind the early objects of Braque and Picasso, the sculpture-paintings of Alexander Archipenko and the Counter-Reliefs of Tatlin. Although they disturbed most critics, they also attracted the attention of Guillaume Apollinaire in L’Intransigeant (28 February and 5 March 1914).

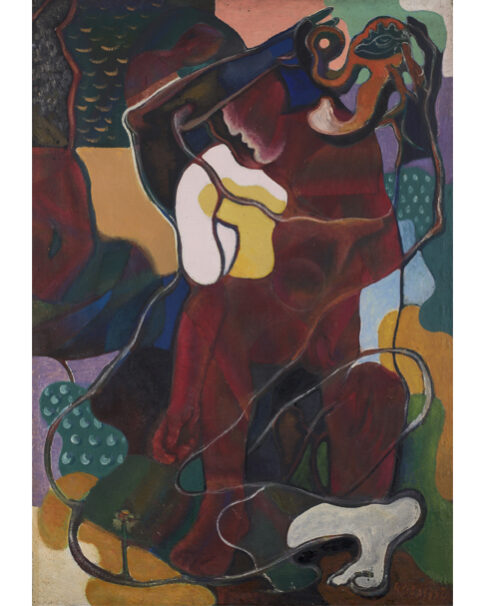

When war was declared, Rossiné decided to return to Russia, first to St. Petersburg, then to Kherson. Later, in the autumn of 1915, he went to Scandinavia and lived in Kristiana (now Oslo). Despite considerable financial difficulties, he continued his experiments in the field of painting, still working on the phenomenon of synaesthesia. In November 1916, he held his first (and only) solo exhibition at the Blomqvist Gallery in Kristiana, where he exhibited paintings a “polychrome palette” (his first invention), which disconcerted critics, alongside paintings inspired by the Möbius strip (1910), characterised by arabesques treated as coloured volumes that curl around themselves in space. The spatio-temporal quality and rhythm of these works that show the painter taking his first steps towards abstraction prefigure Baranoff-Rossiné’s interest in the analogies between painting and music, then also being explored by Wassily Kandinsky, Arnold Schönberg, and František Kupka (in his coloured fugues), but also by the Russian futurists who aimed to bring all the arts into interaction and to embody the concept of the total artwork, if only in Victory over the Sun (1913), a futurist opera by Kazimir Malevich, Mikhail Matiushin and Velimir Khlebnikov. He also developed a “visual-colour projection” device that allowed him to give his first “light concerts” in Kristiana and Stockholm.

With the outbreak of the Revolution, Baranoff once again returned to Russia in order to become involved in the revolutionary movement. This was when he adopted the name Vladimir Baranoff-Rossiné. He taught at the Svomas (Free Workshops) and Vkhutemas (Higher Art and Technical Workshops) and carried out state commissions, while at the same time continuing the chromatic and synesthetic researches that led to the creation in 1920–23 of the “Optophonic Piano,” which “projects into space or onto a screen colours and shapes that move and vary infinitely, depending absolutely, as in the acoustic piano, on the workings of the keys.”[4] . Baranoff’s piano took up the idea of the Père Louis Bertrand Castel’s ocular harpsichord (1735) and Alexander Scriabin’s light keyboard (1915), while responding to the Romantic dream of the synthesis of the arts (Gesamtkunstwerk). Behind the exterior of an upright piano with keyboard, the instrument concealed a mechanism consisting of coloured discs, painted by the artist, complemented by a set of prisms, lenses, mirrors, a light source and a projection screen, which worked thanks to the combined action of the discs and the effect triggered by the keys. The moving images were projected onto the screen to the rhythm of the music produced by the discs. Baranoff-Rossiné explained to Sonia and Robert Delaunay how his invention worked in a letter dated 19 December 1924:

“My instrument […] makes it possible to give free rein, in a way never seen before, to the dynamics of light in colour, something we could only dream of. Now the painter is no longer the slave of the flat surface […] but the master of his desire, of his will. This is where reality lies. An immense field of action for pictorial creation. In one second, billions of pictures, a universal kaleidoscope of the will. The music is certainly a compromise with the public. The real goal – the end in itself – is a painting that is alive in time and not deaf and dumb.”

After registering a patent for his piano in Russia in 1923, the artist gave three “opto-visual” concerts in Moscow in 1924 (Meyerhold Theatre and Bolshoi Theatre), in which coloured lights animated a romantic and symbolist repertoire (Schubert, Wagner, Grieg, Debussy and Scriabin).

However, the hardening of the political regime and the death of Lenin on 21 January 1924 led to his exile from Russia. He settled permanently in France in 1925.

In Paris, he founded the Académie Opto-phonique, dedicated to the union of sound and image, registered a patent for his piano (25 March 1926), and gave concerts in 1928 and 1929 (Studio des Ursulines and Studio 28). His invention paved the way for the musicalism of Henry Valensi and Charles Blanc-Gatti in the 1930s; he was present with them at the Salon de la Peinture Musicaliste organised in Limoges in 1939.

Between 1925 and 1940, he took part in the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes de Paris (1925) and the Réalités nouvelles exhibition (1939) and featured regularly at the Salon des Indépendants. His work during this second and last Parisian period was rather heterogeneous. On the one hand, he continued his various technical inventions (Chameleon process, Mensurator, Multiperco), and on the other he produced figurative landscapes and portraits, compositions influenced by cubism, numerous abstractions, but also canvases with a surrealist and biomorphic tendency – both abstract and figurative – in which we find organic forms close to those developed at the same time by Salvador Dalí, Juan Miro and Yves Tanguy, but also Hans Arp and Fernand Leger. Baranoff never lost his passion for colour and undulating line.

He was arrested by the Gestapo on 9 December 1943 and deported to Auschwitz on 20 January 1944, where he died five days later.

Maria Tyl

[1] In 1912, the artist adopted the pseudonym Daniel Rossiné; after 1917, he began using the name Vladimir Baranoff-Rossiné.

[2] From the Greek for wreath of flowers or garland, title of a collection of verses (1906) by the symbolist poet Valery Bryusov.

[3] “On the Impressionist Exhibition,” in Severo zapadnyi golos (The Voice of the Northern Traps), 12 January 1910. Cf C. Pattu, Vladimir Baranoff-Rossiné (1888-1944), multidisciplinary artist, creator and interpreter within the Russian Avant-garde. Postgraduate dissertation, submitted under the supervision of Dominique Dupuis-Labbé. Ecole du Louvre, 2018, p. 58.

[4] V. Baranoff-Rossiné, L’Institut d’art opto-phonique, 1925.