Kupka’s many extra-artistic interests – anatomy, astronomy, chemistry, natural history, philosophy, the phenomenon of synaesthesia, and esotericism – had long drawn him towards the abandonment of figuration. As was the case for Kandinsky, this transition was directly linked to music, and indeed this constitutes the guiding thread of our exhibition. As early as 1890, Kupka set out to create a musical art, a “sonorous abstraction.” In an interview given to The New York Times on 19 October 1913, he spoke of his ambition to “find something between sight and hearing and […] produce a fugue in colours, as Bach has done in music.” In the 1910s he made his first abstract works, notably Amorpha, fugue à deux couleurs and Amorpha, chromatique chaude which establish a correspondence between rhythm and colour and reject any kind of perspective. The works in this series were shown to the Parisian public at the Salon d’Automne in 1912.

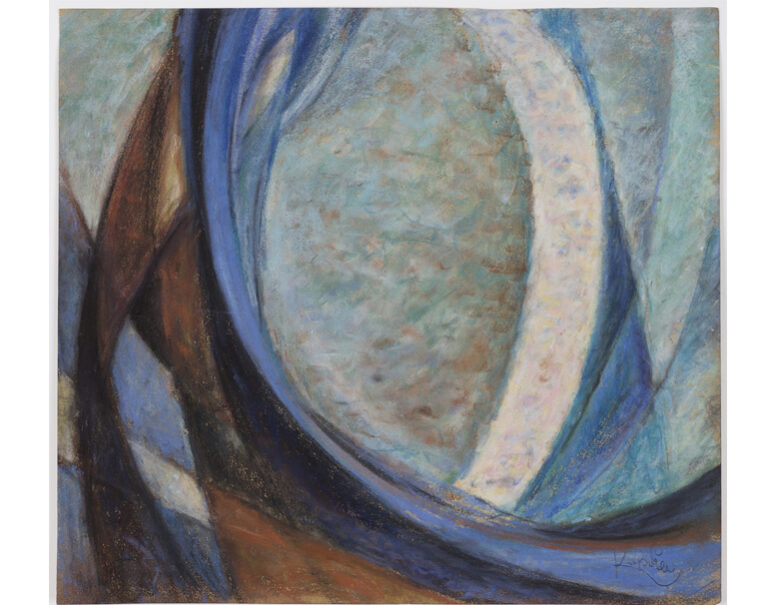

At the start of the 1920s, the artist was particularly interested in the relation between aesthetics and nature, science and art. His work was dominated by irregular and organic forms, taking inspiration from physical phenomena embodying vital forces. In the series Autour d’un point which constitutes the culmination of his highly conceptual development, circular forms with a threefold symbolic resonance – esoteric, cosmic and biological – interact, their curved, coloured forms determining the singularity of the formal and spiritual abstraction championed by Kupka ever since his early years.

Towards the end of the decade, after a period of crisis, the artist was looking for other stylistic solutions and took the path of geometricization and formal simplification. On one side, he reintroduced into his works elements drawn from reality and discovered the machine aesthetic and the world of jazz, which enabled him to go back to older questions touching on movement and rhythm. On the other, he joined his friend Theo van Doesburg within the Abstraction Création group, working for the international recognition of geometrical abstraction, which at the time was marginalised by Surrealism but also by the revival of interest in realism. The works from this period can be considered as a prefiguration of minimalism in the art of the 1960s.

The counterpart of this profusion of colours, characteristic of Kupka’s work, is his distinctive use of black and white, and the highlighting of their antagonism. We will therefore allow considerable space to the album published by Kupka in 1926 under the title Quatre histoires de blanc et noir (Four Stories of White and Black), which constitutes a kind of summing up of his abstract formal experiments, a summary of his art since his rejection of mimesis.

The forty gouaches that we are exhibiting all come from the sources closest to the artist himself: his collector and patron friends (Jindrich Waldes and Jack Kouro), Jean-Pascal Loriot – a publisher and printer close to Eugénie Kupka (the artist’s wife) –, and Katia Pissarro – a gallerist and dealer who obtained works from Loriot and the Karl Flinker gallery, who, when the artist died, represented his figurative work and works on paper (alongside Louis Carré, who handled the abstract canvases).