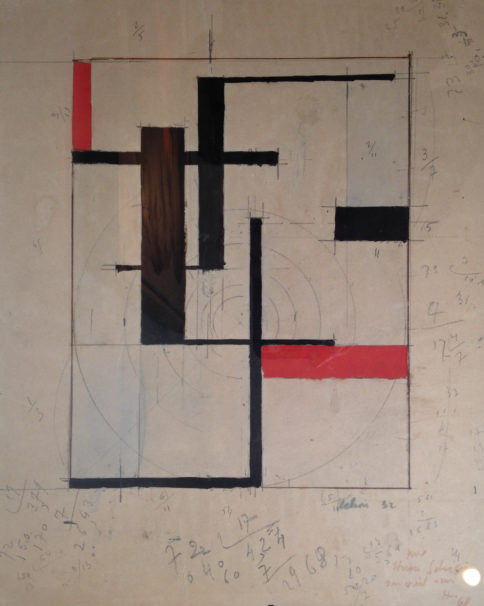

Born in Normandy in 1904, Hélion initially opted for architectural studies in Paris. After a brief spell as a painter in Montmartre in 1929, he joined Théo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian in a move towards geometric abstraction. A member of the Art Concret group, he also helped found the Abstraction-Création collective, home to the leading abstractionists of the interwar period. A friend of Calder, Arp and Giacometti, he was also close to Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp and Victor Brauner.

In 1929 he began his series of Notebooks, reflections on painting that he kept up until 1984. He was also close to the writers of his time: Francis Ponge, Raymond Queneau, René Char, André du Bouchet and others, who remained part of his artistic vocation.

In 1934 Hélion moved to the United States, where he became friends with Duchamp and one of the country’s foremost abstractionists. A leading figure on the American art scene, he also served as an advisor to America’s most eminent collectors.

Even so, in the mid-1930s the growing liveliness of his forms presaged a return to the human figure. And in 1939, just when abstraction was beginning to dominate the international scene, his intuition led him increasingly towards figuration and “the real”.

Alerted to the fragility of things by the outbreak of the Second World War, he set about applying his abstract language to a reconstruction of the image, the result being everyday street scenes stripped of all sentimentality.

Calling a temporary halt to his career as a painter, Hélion joined the French army, but was taken prisoner in 1940. Initially published in 1943, They Shall Not Have Me, his account of his escape, was recently translated into French and became a best seller.

Back in France in 1946 and married to Pegeen Vail, Peggy Guggenheim’s daughter, he struggled to find his place on the Paris scene, but came up with a new form of figuration via a range of styles and subjects: the nude (Nu renversé, 1946), the landscape (Le Grand Brabant, 1957), the still life (Nature morte à la citrouille, 1946 and Citrouillerie, 1952), allegory (À rebours,1947, Jugement dernier des choses, 1978–79), history painting (Choses vues en mai, 1969) and studio views (L’atelier, 1953 recently acquired by MAM with the aid of the Amis du Musée d’Art Moderne and the Fonds du Patrimoine). Paris, street life and minglings of dream elements proved an inexhaustible source for his “prose of the world”.

Late in life, with his sight failing, his work became a deliberate miscellany of the motifs that had always haunted him. His painting oscillated between derision and gravity (Le Peintre piétiné par son modèle, 1983) and between dreams and joyful dazzlement.