Tibilissi, 1907 – Montrouge, 1988

From the early 1930s to the 1980s, Vera Pagava deployed her pictorial universe first in classic genres such as the still life and the landscape before turning, in 1960, to another genre,

abstraction, that would occupy her for the rest of her life. Throughout her discreet career, shunning the art world and its social round, she maintained a constant link with the avant-garde of the day while deliberately sticking to her “ancient” medium and support: oil paint, applied by brush to a canvas on a stretcher or, more seldom, a wooden panel. With the detachment afforded by history, the mysterious world of her paintings, with their vibrant, luminous purity, can be seen as truly remarkable. Apart from a monumental wall piece made for Expo 58 in Brussels and a series of stained-glass windows and furniture for the church of Saint-Joseph in Dijon in 1986, Pagava’s oeuvre consists of a corpus of paintings that deliberately ran counter to those pictorial practices that were ideologically bent on restoring life to a form of painting that modernity had declared dead and buried and that, to do so, deliberately indulged in the spectacular, if only in the use of new mediums and supports or emphatic large formats, or again in the boldness of the motifs. Exiled from Georgia, where she was born in 1907, Pagava moved to Paris in 1923. After several courses in applied arts she completed her artistic education at the very elitist Académie Ranson from 1931 to 1939, frequenting artists such as Etienne-Martin and François Stahly, and forging un unshakeable friendship with Vieira da Silva. Though born into an affluent and cultivated family, Pagava’s life in exile was precarious and in her early days she took on work such as weaving and designing ornamental motifs in order to keep body and soul together. She was also developing a pictorial language with post-Cubist and Surrealist overtones. These were already manifest in her first works on canvas of the 1930s, such as Perroquet (Parrot, c. 1935) and Forme abstraite avec guitare (Abstract form with guitar, 1938) . Their schematisation, which could already be described as “biomorphic,” as in Calder and Miró, evoked the curves of life forms and subtly led its subject to the limits of identifiability: “she questions the limits of the eye,” wrote Guy Weelen.

From the outset, her language was marked by a pronounced taste for certain artists, particularly Giotto, Cimabue and Fra Angelico. Their skies but also their perspective and schematic modelling, which could be described as pre-Renaissance, also struck her as being suited to rendering forms that were in space but not illusionistic. This is the case, for example, in Campanile (Bell Tower, 1957). Her way of representing emptiness and volume, for example, in still lifes such as Nature morte sur table (c. 1945-1950) stemmed from what one could call a primitivist, sculptural approach, by virtue of which she could be compared to Constantin Brancusi. Under Pagava’s brush, slices of watermelon, glasses, plates and table are no more

than zones of colour. In these pared down spaces there is no effect of modelling, no play of shadows to create depth or offer a mimetic perspective, or at least some illusion the eye

can believe. Another thing she took from the Italian proto- Renaissance artists was the layering of space. This is found in the paintings with subjects that are primarily architectural, such as La cathédrale de Barcelone (Barcelona’s Cathedral, 1955), then fully abstract, as in Sur la ville (Ville lumière) (On the City or City of Lights, 1963). She also understood the beauty of the way their frescoes had aged over the centuries and, in works like Lagune II (Lagoon II, 1964) , Vespéral (c. 1965) and Saint-Malo (1971) she integrated their slightly muted palette, that veiled luminosity and the flat patches of colour corroded by time.

At her first exhibition at Galerie Jeanne Bucher in 1944, alongside Dora Maar, she received encouragement from Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, who no doubt appreciated her refined schematisation and sober palette. As to other contemporaries, the influence and friendship of artists like Max Ernst, Giorgio De Chirico and Yves Tanguy may also be significant, reflecting Pagava’s efforts to bring forth a strange universe, devoid as ever of any obvious narrative or meaning. Within these worlds, the artist constantly questioned the link between each painted form and the object or image, but also their physical, tangible, even geographical reality, and did so progressively through to the 1950s, when the spiritual quality of her art seems to have truly broken free of the object and attained a certain interiority. As she wrote very early in her career, in a letter to her friend Roger Hilton, “painting reflects us, it is a miraculous mirror in which the outside world sees our inner world.” Pagava’s still lifes have a kind of purism of penumbra, which distinguishes them from the purism of Amédée Ozenfant or the light-bathed ensembles of Giorgio Morandi. La Dame aux étoiles (Woman and Stars, 1946) gives us a better sense of this Georgian artist’s singularity, notably by virtue of the references that come together here: a female figure, taken from Woman before the Rising Sun (1818) by Caspar David Friedrich, but with her body now broken up into geometrical zones of colour like a Malevich peasant, has her back to us, being absorbed in the contemplation of a midnight-blue sky where three glowing stars (no more) create a slightly bluish halo. By a strange twist, one of them shines its light onto the ground, just next to the figure, like a theatrical tracking spot that has missed its object. This strange luminous manifestation is in fact surprisingly close to the speculations of László Moholy-Nagy regarding light and multidimensional space. There are a number of precedents for this modality in Pagava’s earlier work, including still lifes and it would develop extensively if in different, more or less geometrical forms from the mid- 1960s to the end of the 1980s.

This aesthetic orientation also prevailed in Pagava’s work after 1960, when figuration became, in her eyes, a “crutch” that her art could now do without. The break with the referenced

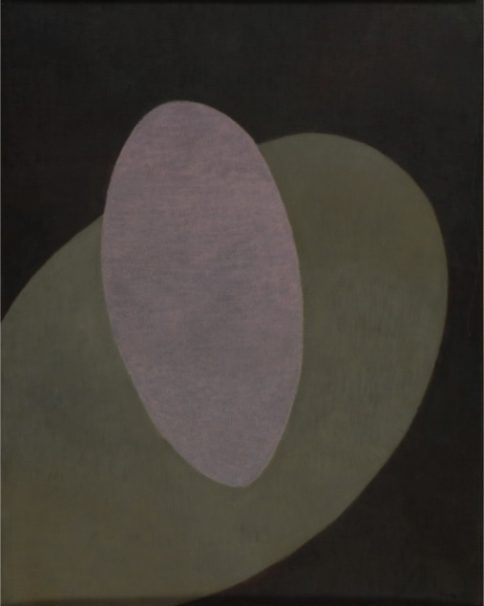

subject, which had been long coming, was finally consummated (that same year, Jacques Lassaigne, who was a great support for the artist, spoke of the “bare reality” of her earlier “imaginary landscapes”). In this respect, the titles she gave her paintings, often referencing actual geographical places, were now only an indexical presence. Reminiscent, here and there, of the Rythmes colorés by Léopold Survage or certain simplified forms in Russian Suprematism, from Kazimir Malevich to Ivan Klyun, all of them airy, even cosmic, and steeped in spirituality, Pagava’s work oscillated between the mental structure of geometry and the curved entropy of life forms. Beyond these connections, the chief characteristic of this Georgian artist’s work, especially after 1960, was the silent suspension of enigmatic entities, of forms whose surfaces and contours, palpitating and vaporous, surely make them celestial bodies floating free of both the terrestrial regime and of the signifying world. Deployed by the artist in a space that is at once frontalised and without limits, like the deep, almost absolutely

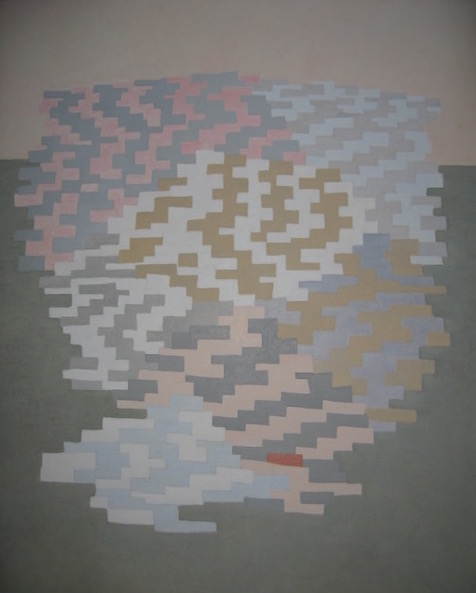

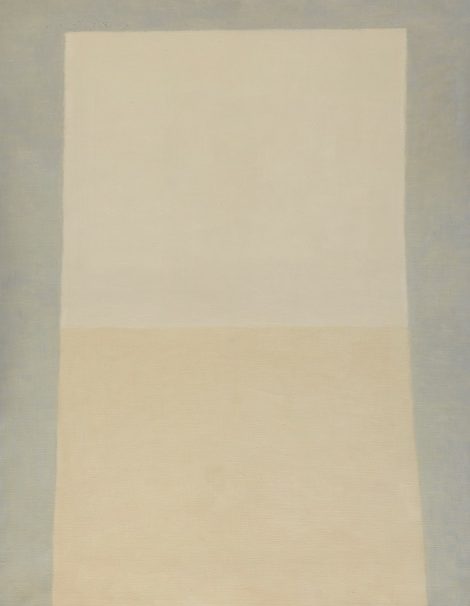

black one of La nuit bois de Céré IV (Night, Céré Wood, 1964) or the explicitly “alpine” one of Vertige (Vertigo, 1979) , these elements conjure up the opposing feelings of sublimity and intimacy, as in Mark Rothko’s most atmospheric compositions. Where William Turner transcribed the dazzling light of the sun. Where Robert Delaunay and Giacomo Balla painted the radiance of electric light with its bright colours and sharp rays, Vera Pagava preferred an indirect, almost subjacent light, as if filtered, in most cases by several layers of oil paint or, in the case of a remarkable series of watercolours, resulting from the complete immersion of the paper, as in Lagune II (Laguna II, 1966) , the luminosity of which recalls

Douce, an oil on canvas from 1973. The watercolour, which in fact was exhibited amidst a set of works by the artist in the French Pavilion at the 1966 Venice Biennale, is simply a gentle

transition from the clear blue of the water to the luminous yellow of the sun. The surface is now merely an atmosphere, a pure halo, freed from its formal core. But this attraction to pure light and immateriality did not keep her from being grounded in the real. In this respect, the composition of the painting Un rêve (A Dream, 1970) was determined in part by an irregularity in the weave of the canvas, which determined the position and the center of an abstract, polychrome silhouette. The eloquent silence of works like Ascension (1976) or Orage sur la plaine (Storm on the Plain, 1963) thus partakes of an internal communication, one positioned beyond language, without the help of the signifier. The titles, which are mostly descriptive, evoke an action, an atmospheric event, a city, a cathedral, a still life, a simple stone or even a battle. But these are false leads. The viewer’s relation is strictly to the painting, and the experience that ensues is perfectly autonomous. With the floating pyramids of his enigmatic Les Origines series, made in around 1910, Paul Sérusier was trying to attain “an equilibrium that anyone looking at the work can feel […] in any culture or period.” In the same way, the rich arborescence of the primitive forms made by Vera Pagava developed this simple idea: the painted form is not the support of a narrative, but the expression of a simple formal tension free of anecdote, and universal in its scope.

Matthieu Poirier, in Vera Pagava, exhibition catalogue, Galerie Le Minotaure, Galerie Alain La Gaillard, Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jeager, 2016