Between 26 March and 4 June, the two spaces of Le Minotaure and Alain La Gaillard galleries are hosting a monographic exhibition of Issachar Ber Ryback (1897-1935), a major artist of the Jewish avant-garde of the years 1910–20, a pupil of Alexandra Exter and one of the leading figures in the Kultur-Lige, an organisation created in Kyiv in 1918 and dedicated to building and giving a voice to a new Jewish culture, based on the synthesis of national and global cultural traditions. The exhibition is organised in collaboration with the Ryback Museum (Bat-Yam, Israel) and the Museum of Jewish Art and History (Paris). Starting on 8 March, the latter museum is also presenting its own exhibition of Ber Ryback’s work, for which the Bat-Yam is lending five major paintings from its collection. Five other pieces will be exhibited in the two Parisian galleries.

The exhibition focuses on the avant-garde period of Ryback’s work, from 1916 (the year he travelled with El Lissitzky to Belarusian villages to sketch synagogues and collect and copy Jewish folk art) to 1926 (the year of his arrival in Paris). It is divided into six parts relating to different aspects of the artist’s work.

The first part looks at the publishing projects of the Kultur-Lige and the drawings of Jewish folk ornaments made by Ryback during his trip to Belarus with El Lissitzky in 1916 – a trip that he continued, alone, between May and September 1917 at the request of the Ukrainian Central Committee for the Protection of Historical and Artistic Heritage. Following a method of his own invention, Ryback essentially reproduced the tombstones of ancient Jewish cemeteries, bringing back rare and precious motifs from Jewish folk art. He was inspired by a belief in the modern artist’s organic link with the past and the artistic tradition of his people. Sketches from this period would fuel his later creativity, including illustrations for books, especially in the years 1917-19.

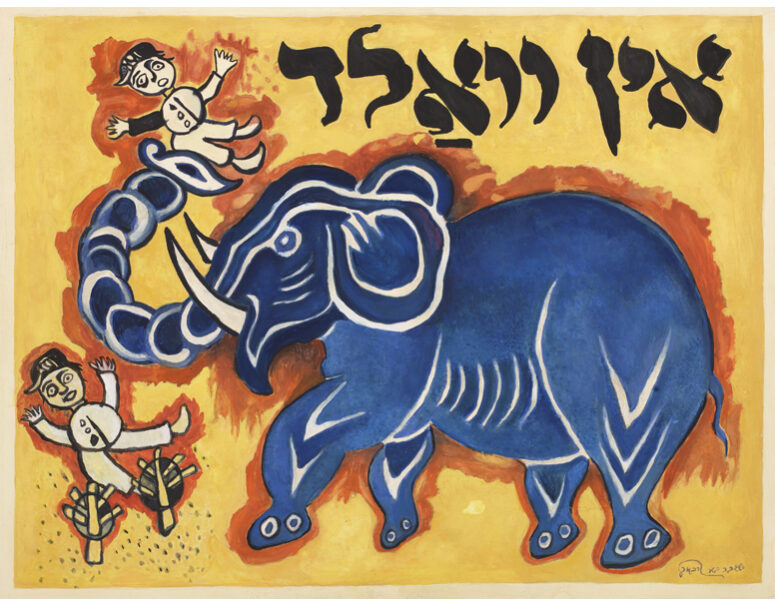

In the second part we see the illustrations Ryback made in 1922 for Yiddish children’s books, including Miriam Margolina’s Mayselekh far kleynininke kinderlekh (Little Stories for Children) and Leib Kvitko’s In vald and Foyglen. Ryback’s graphic approaches to these projects show his different ways of using images and motifs from Jewish folk art. These illustrations occupy a special place not only in the artist’s graphic corpus, but also in the history of book arts, Jewish and global. Their key innovation was to use the style of children’s drawings, which was not done by other avant-garde artists, including the Russian Futurists, who also illustrated books for younger readers. As the artist’s widow recalled, Ryback “believed in the principle that children should be given drawings of the kind they could make them themselves. And children accepted his drawings as their own. Ryback was very happy when Dovid Bergelson’s grandson, Leïvik, said to him one day: ‘Daddy, I can draw like Ryback too.’ The children understood his art and loved him as a person.”

The third part is dedicated to the “Shtetl” album (inspired by the Jewish settlements in Eastern Europe before the Second World War), published in Berlin in 1923 and presenting various characters and scenes from the life of these communities. The drawings in this series are probably Ryback’s best-known works and are often seen as works of folk art. In them, the artist performs a kind of rehabilitation of the shtetl. Whereas the shtetl was commonly represented as a world of backward “little people” labouring under the yoke of obscurantism and superstition, a dark and dreary place, devoid of bright light and fresh air, for Ryback it was not only an object of artistic and aesthetic admiration, but also a world full of vital energy. The paintings from 1917 depicting villages and genre scenes are full of qualities. Moreover, while retaining authenticity and “ethnographic” accuracy, recording the details of the real places and their inhabitants, Ryback does not make them concrete, but revisits them in a general image. In his imagination, the shtetl is the home of an original civilisation, in which it plays an essential role, just like the role played by cities in the cultural development of ancient and Christian Europe.

The fourth exhibition will show works from the “Pogroms” series, a bloody chronicle of the wave of pogroms that swept through Ukraine in 1919, during which Ryback’s father was murdered. The traumatic nature of this event for the artist is reflected in his extraordinarily heartfelt watercolours depicting bloody scenes of violence between the pogromists and their victims, which are harrowing with their naturalism. Ryback draws on real events and documentary evidence, channelling them through popular, “folk” imagery that harks back to both Ukrainian imagery and the tradition of Yiddish Jewish folk literature, which preserved in the collective memory the story of Jewish martyrdom and death for the faith during the time of massacres and persecutions.

The fifth part of the exhibition will show Ryback’s pictorial work, which explores his idea of combining Jewish folk art with the artistic avant-garde, especially cubism and expressionism. The critics of the day recognised his formal mastery, his art’s “resonance” with the spirit of the times, the importance of the themes in his works – their depth and singularity. Articles published at the time considered Ryback’s cubist paintings, his “mystical abstractions,” as a milestone in the development of contemporary Jewish art and as a new and original version of a popular modernist style. His artistic discoveries are inseparable from the achievements of the new Jewish avant-garde art and his name should figure among its greatest representatives, alongside the likes of Marc Chagall and other very famous Jewish artists of that generation.

***

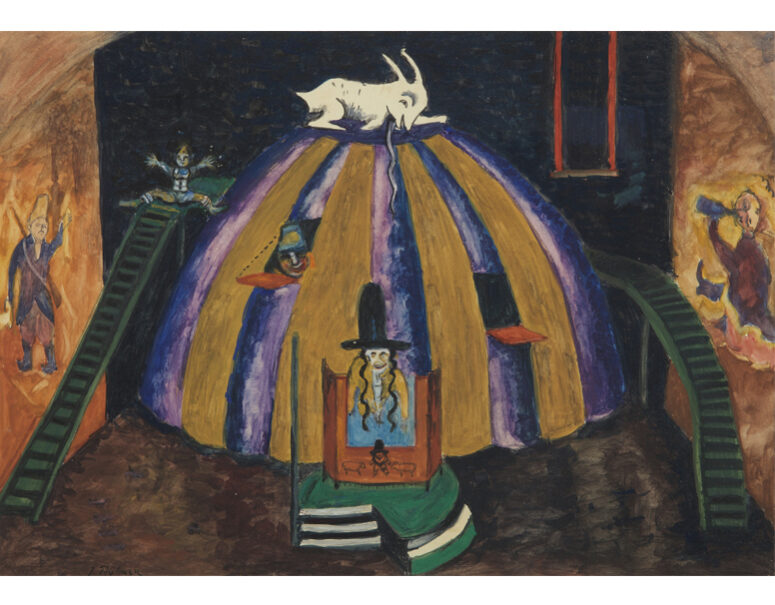

Finally, the last part of the exhibition is devoted to stage and costume designs for Yiddish theatre, another important activity of Ryback. His interest in set design began in Kiev, when he attended the studio of Alexandra Exter, who was considered one of the most radical and original reformers of Russian theatre staging at the time. Ryback made his debut as a set designer at the Kultur-Lige theatre studio. For its first production, the studio chose the symbolist play Mashiach ben Yosef, by Beinush Steiman, for which he designed the set and sketched the costumes sketches and stage scenery, in keeping with the broad principles of stage design laid down by Exter: the movement of coloured surfaces and the construction of three-dimensional scenery made up of platforms of different levels and depths, allowing for several simultaneous zones of theatrical action. He developed these researches in Moscow in 1924 and in Kharkiv and Minsk in 1925, again for the Kultur-Lige. The costumes he designed for the characters were particularly inventive and witty, often evoking the masks of Commedia dell’arte. Ryback did not limit his role to an auxiliary function, of designing a form for the director’s idea, but actively influenced the entire production. By shaping the stage space, he effectively determined the style of the show, the dynamics of the individual zones of action and the plasticity of the actors’ movements. This creative stance was in keeping with the main trends of avant-garde stage design, which Ryback developed in an original direction.

In 1926, the artist moved to Paris, where he worked until the end of his life (1935), developing a style closer to the School of Paris.

The exhibition will be accompanied by an important – and the first – monograph on the artist in three languages (French, English, Russian) with texts by Hillel Kazovsky, a specialist in Kultur-Lige artists, and Hila Cohen-Schneiderman, director of the Ryback Museum.